by Allyson Wuerth

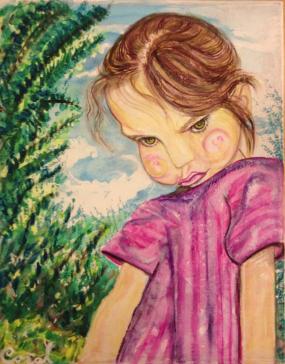

She came into this world silently, too. We held our breaths and waited for the sharp cry that came only after doctors intervened. Her lungs pulling in air and screaming only when her life absolutely depended on it. Such a birth was meant to foreshadow the way we came to know this girl.

As she grew, we noticed that she wouldn’t speak outside our home. At all. She’d freeze, attach herself to our legs and whimper. Coupled with, what people came to call, her “shyness” were articulation problems that went beyond that of an average 2.5 year old. She had a language of her own, and my family and I became translators of a stony language. “Mem” she would say, when she meant “friend.” Her brother Tristan she would call “Chichin.” “B”s and “D”s, “M”s and “F”s, “K”s and “T”s, “L”s and “W”s all whirled around inside her head and settled into the wrong words. Family and friends convinced us this was the problem. She had the voice but not the language, the desire but not the words. The pediatrician said she was literally tongue-tied, so we scheduled the procedure to have her frenulum clipped. When the words still did not come, the doctor suggested that we get her ears checked. But when she would not acknowledge the sounds provoked by the audiologist, he pronounced her “too young.” “Come back in another year,” he said.

Her silence was under my skin, in my blood. Hadn’t our hearts beat together for nine months? Hadn’t she grown inside me, shifting her weight against my ribs? Hadn’t her heartbeat been enough to assure me of the room she would need in this world? The space she would fill? I felt her silence as a betrayal. But by whom? Of whom?

Our pediatrician was hesitant to recommend therapy—firmly stating that Sawyer was too young to be expected to communicate with strange adults. I wanted badly to agree, to believe that with time my tiny girl would smile at people and tell them her name when she was asked it. That she would volunteer stories or hold hands with little girls on the playground. But she’d never even spoken to my grandmother. My grandmother’s declaration still hangs over me, “She just don’t like me, doll.” There was no arguing. For my grandmother, this was just the way it was with Sawyer.

Then, after nearly a full year of pre-school, the words of Miss Mandy, Sawyer’s pre-school teacher, urged me to push harder, “We’ve never even heard her speak.” I was imploding. Really? No words? Never? As in not EVER? Miss Mandy added, as if we were two ladies gabbing over tea, “Yeah, we keep saying we wish some of these other kids were as quiet! Think of the self-restraint a 3 ½ year old must have to not speak all day!”

I called the pediatrician that evening, “I think my daughter has selective mutism.” I spit the words out and let them sizzle between us. And her own silence told me that she–like so many doctors, teachers, therapists, I’ve spoken to since—had no clue what I was talking about.

Selective mutism. I first heard those words, all hushed and breathy sounding at a holiday cookie swap in 2011. The conversation caught my attention—some silent girl–a girl whose mother also affirmed, “She’s a chatterbox at home, I swear!” This one a little older than my two and a half year old. Somebody mentioned a child psychologist. Another the diagnosis. I listened closer. This girl sounded so much like mine. Mine too looked through strangers and family as if they were ghosts. Mine too chatted happily in our house only to go out into the world pale and blank. I kept those two words–selective mutism– within me for another year before I unpacked them, left them at the ear of the pediatrician. Like the girl’s mother from the conversation I overheard, I too knew the difference between shyness and the eeriness of a silence that ran much deeper.

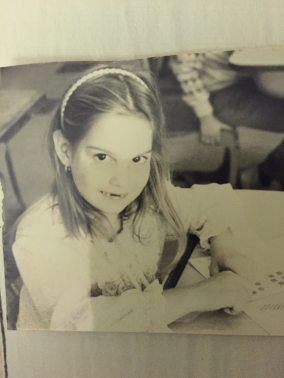

To make myself understand my girl, I had to go back to 1984 where I am walking up Davis Rd. with some neighborhood boy. He has an idea: let’s throw acorns at cars. Even though his face is too blurry to name him, his words are clear as if they were spoken only yesterday. Let’s. Throw. Acorns. At. Cars. The first two cars don’t stop. The third does. A man gets out. He has shoulder length feathered brown hair. His eyes are invisible. The neighborhood boy yells for me to run. He himself disappears into the fir trees between two raised ranches. But I am frozen. I try to scream, but no words come out. No part of me is willing to move. The man chases the neighbor boy through the trees, walks back to his car, and drives off. And there I am. Still.

Thirty years later, this moment is etched into my heart and it has the ability to change my heart’s rhythm and stumble into its beats. Why didn’t I run? Scream? Even at six, I wondered if I would ever be able to defend myself. Why had my own body betrayed me when I needed it most? As the car drove off, slowly my limbs unfettered themselves. The first few steps I took were numb, heavy, and frustrating. I wore black patent leather Mary Janes, but the feet inside them didn’t seem my own. It was the first time I remember being conscious of my own consciousness. And from that day I decided three things would always be true:

- Somewhere in the world there was a better version of me.

- Somewhere in the world there was an evil version of me.

- One of us wasn’t real.

When you imagine a body wired this way, silence becomes palpable—and your body is a whisper that almost no one can hear.

For the next two years we spent our Thursday afternoons in Dr. Schiller’s small New Haven office filled with Playmobil toys from the 70s, baby dolls, play-doh, and an old wooden doll house. At first it was the three of us—me, the collector of her whispers. Later, I sat in the waiting area and Dr. Schiller and Sawyer negotiated this tricky path of communication together.

Later, in my bedroom we sit like old ladies folding laundry on my bed. I ask her if it’s okay for me to ask her a few questions. “About what?” She asks.

“Your talking,” I say. She looks at me uncomfortably and says okay.

And it is uncomfortable, this interview between my daughter and me. She is shifty and covers her face with a pillow. She tells me that talking to her teacher is scary, that sometimes she knows the answer but it’s too scary to say it. “What’s so scary?” I ask.

“I don’t know. Just talking.”

“Is it scary to talk to mommy?”

“No.”

“Daddy?”

“No.”

“Tristan?”

Again her answer is, “no.” I ask her about friends and classmates. She tells me sometimes it is scary to talk to them, but not mostly. I ask about Alexa, her close friend from class.

“No. It’s not scary to talk to her.”

“Why?” I ask.

“Because she’s quiet…like me.”

And so, we will navigate this silence as one, she and I.

Six years after my daughter’s birth, I sit with her after kindergarten graduation. Her classmates are busy about the room, carrying small plates of grapes and brownies. They squeal, the girls in their frill. But mine sits in her chair, mute. Stone-faced. She pulls me down beside her and whispers in my ear, “snack.”

“Let’s go together,” I say back. She shakes her head. So I collect brownies, grapes, a cup of juice. I hand them to her and she tells me she is tired. She wants to go home from this party she’s been looking forward to for the last few weeks. And so, we gather her things: the papery blue graduation cap, the brightly painted art, her backpack—these final bits of a school year. I say goodbye for her: “Sawyer hopes you have a great summer!” “Sawyer really liked the grapes you brought.” I’d be lying if I said this didn’t unhinge me, this speaking up for a girl perfectly capable of speaking for herself. What must that be like—hearing your own voice filtered through your mother’s body?

But none of it matters. Every day I learn new strategies to help her communicate, to mitigate her social anxiety.

Along with this truth, she’s left kindergarten forever.

About the Author:

Allyson Wuerth is a co-editor of Tell Us a Story. She is a mom, a wife, a high school English teacher, and a writer. She has published poetry in several literary magazines, and has poetry forthcoming in the anthology, Verse Envisioned: Poems from the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette and Works of Art They Have Inspired. You can read her other two blog posts, The True Story of Why I Hate Math , Two Years and 20 Miles from Sandy Hook, and What we Miss Most by clicking these links.