by Will Brooker

I used to keep a diary. A diary is a map of your old life.

I used to live in Cardiff. On Connaught Road. Can you see it, on the map? Strung onto that constellation of resonant names: sapphire, topaz, silver, planet, emerald, star. Like a science fiction universe: a map of manyworlds, of infinite earths. A roll-call of superheroes.

Wait, Connaught Road isn’t on that map – that photocopied and enlarged A-Z from fifteen years back. Wait while I…

Wait. Here it is. Sometimes the past slips and skids away.

Here it is. Here’s the street where I lived. Flat 8, 97, Connaught Road.

But that was 1998, and this story begins in 96. Let’s start again.

I used to keep a diary. I’ve kept many diaries (though some are lost).

I’ve kept many diaries.

This is the one I should have started with.

This is the one. This is the place where it began.

Cathays Terrace is a scruffy, scrubby long road, five minutes from Cardiff University. You could tell how long people had lived there by whether they could pronounce the name of the next street, Crwys.

Cathays itself is one of Cardiff’s student zones. It has a tiny railway station, the size of a tilt-shift miniature, where trains stop outside the undergraduate club, The Terminal.

I’d come up from London in 96. I’d grown up in London. Cathays – and the surround of Cardiff itself – seemed a small world, to me. It suited me perfectly. I felt I could master its map.

That was arrogant. But, you know. I was twenty-six. When else can you be arrogant?

Now we begin. (And it’s my story, so I get captions and a narration, obviously.)

Wait. I was still blond at this point. My hair was yellow like a block of vanilla ice cream.

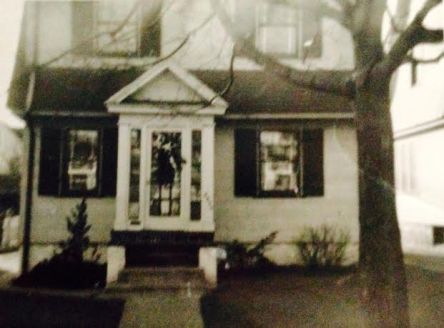

It doesn’t look like much. They film Doctor Who around here now, and pretend it’s London, but it doesn’t look like London; not even the scruffy parts of London I was from. The houses – even the windows and doors – are smaller. The sky hangs lower, always threatening rain.

The picture above doesn’t actually show my road, Cathays Terrace. I had to manoeuvre Google Street View around the corner and swivel its virtual camera back, to find my own origin point. That window in a white wall. That’s where I stayed.

It was a tiny room – a tiny room divided in two with a thin partition. People joked that it was my Batcave, but I used to call it my cell. There was a shower in a cupboard and I shaved at the kitchen sink, using a plastic mirror propped against the taps.

There was no internet – no personal internet, no going online at home. But the university had 24-hour computer rooms with sluggish 484s, scattered around the city, and I knew where they all were. I added them to my map. I spent twelve hours there at a time, 5pm to 5am, and walked home at sunrise; I slept until 10.

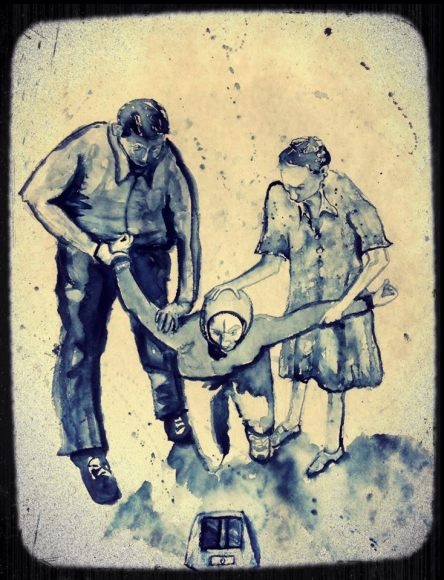

Social networking then was done through notes, postcards, landlines. Somehow – because I was from London, because I was 26, because I was doing a PhD (because I was doing a PhD on Batman) I became the kind of social kingpin I’d fantasised about when I was a sixth former, watching 1980s party movies. Those diaries are a collage of phone numbers with lipstick prints.

What can I say. I’d spent my teenage years reading feminist science fiction, programming in BASIC and doing my homework. I’d spent most of my early 20s painstakingly plucking my eyebrows and being chatted up by businessmen in cross-dressing clubs, like someone from a Lou Reed song. Now Cardiff offered me the chance to be a kind of small-town Bruce Wayne. It was a fun role to play, at the time. It isn’t an interesting story to tell.

What’s more interesting is that I was only this poor-man’s Bruce Wayne by day – and for the sociable part of the evening and night. Nightlife, in Cardiff at least, ends by about 3am. The day doesn’t start – the cleaners don’t wake up and leave for work – until a couple of hours later.

In that time – during that unsociable slice of night – you can be almost alone in the city. And in a small city, you can cover a lot of ground within two hours. You can get a lot done.

You can cover a lot of ground if you run. And I ran every night.

Of course, people asked me if I wanted to be Batman; if I had the costume, if I had the car. I denied it, because look at the Batman everyone knew, back then.

A strange thing happened, though: the day after I saw Clooney as Batman at the Cardiff Odeon, I went to another film called Metroland, at Chapter, the city’s art cinema – on the outskirts of town, across a river bridge, hidden at the end of a park.

A strange thing sometimes happens, in diaries; especially diaries with thin pages.

One page sometimes bleeds through to another.

Today is the ‘tomorrow’ you look forward to.

Anyway. This wasn’t my Batman, at the time.

Officially, I embraced the Batman of multiple, mosaic earths. My kitchen was plastered in postcards of Adam West. One metre along the wall, where it became my living room, there were framed images of the Animated Series Batman and Frank Miller’s Dark Knight of 86. Another few steps across my cell, and the mantelpiece by the shower cubicle was decorated with a print of Tim Sale’s Long Halloween Batman from the late 1990s.

But these weren’t really the Batman I connected with; the Batman I aspired to be. You couldn’t be those Batmen. They were too professional, too slick, too rich.

But you could be this Batman, from Brian Augustyn and Mike Mignola’s Gotham by Gaslight. He wasn’t a billionaire or a technocrat. He was just wearing a big coat with the collar turned up, heavy boots, and leather gloves.

I already had a big black coat, which I wore with the collar turned up. I bought black heavy boots and black leather gloves. That was easy: The Matrix had just come out, and Neo-style outfits and accessories were popping up in the indie shops next to Spillers Records, on Canal Street. You couldn’t buy Batman t-shirts at the time, so I scanned a logo from the back of a comic and had it printed onto a tight grey top.

I still went out, as normal, as a civilian – to the Terminal, to the Rummer, to the Clwb Ifor Bach – then came home at 3am, got changed and went out again. I lived mainly on oranges and bread; baguettes from the Tesco bakery at opening time, shoved still-warm in my mouth as I walked home. I started sleeping until 2pm, waking myself with espresso the colour and thickness of tar.

In the afternoon, I trained. I stopped listening to indie pop and began lifting weights to a soundtrack of Tricky, Chemical Brothers and Prodigy.

After a while, I stopped going out – that is, I stopped going out socially. I just went out…antisocially.

When I say I went out: I mean, I went out of that window. That back window in the photograph. And across the garage roof below, along the wall, and down to the street.

I knew a lot of people and a lot of places. I had a lot of contacts, a lot of keys, a lot of door codes. I was twenty-six. It wasn’t a large city. I could cross it in twenty minutes.

I didn’t do anything wrong. I was being Batman. I was gathering information. That’s what Batman does: he’s a researcher.

I didn’t do anything wrong. At least, I didn’t think I was doing anything wrong.

Something happened, later, but it really wasn’t my fault.

I stopped the training, the night-time patrols, but not because I’d done anything wrong. I stopped because I’d become too well-known. First in Cardiff, after I gave a lecture on the Dark Knight from 1939-99 – Y Marchog Tywyll was the headline (in Welsh) in Gair Rhydd, the student newspaper – and then beyond, as the media picked up on the story that someone was doing a doctorate in Batman.

I’d enjoyed being a local face, a familiar name on a small scene. Suddenly I was getting calls from the BBC and invitations back to London to appear on TV. For the first time in my life, companies were paying me to take cabs and stay in hotels.

I moved to a far larger flat on Connaught Road. I had a steady girlfriend now. I bought things like matching cups and plates. Fridge magnets. Bottle stoppers. Things like that. I finished my PhD. I applied for jobs.

I got a job. It wasn’t as easy as that makes it sound, but I got a job. I moved back to London. I became an assistant professor. My thesis was published as a book. I became respectable, on the surface at least.

It was the twenty-first century now. People had internet at home. I joined discussion forums. I checked them with my first coffee of the day, before work. I wore a suit now.

Barbelith was a progressive, intelligent site named after a scarlet satellite – a cosmic stoplight – from Grant Morrison’s comic book series The Invisibles. It was a supportive community, but tightly run and strictly policed. I posted on there for many years, first as myself and then, changing persona to give myself more freedom, under a female name. That name may have saved my career.

Barbelith was tightly run and strictly policed, but someone managed to sabotage it. His name circulated on the discussion boards like a curse, a word of power. His original handle was ‘DisInformation’, and people even became superstitious about invoking it: they referred instead to DisInfo, or The Formation.

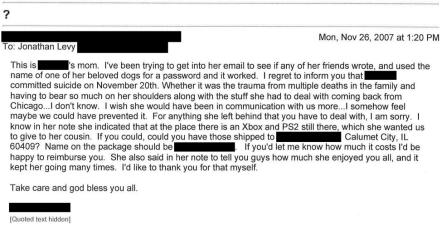

I can’t remember the details of his strategy: a back-door exploit that took advantage of the ‘forgot your password’ facility, and mailed the details of regular board members to his own multiple accounts. But the community lived in fear of this guy, who had discovered the real identities behind their codenames and contacted their employers.

Nobody was doing anything wrong exactly. But it was a board based on Grant Morrison’s The Invisibles, and most everyone on there styled themselves as a member of Morrison’s subversive superhero group, a real-life extension of the fiction. There was a lot of discussion about chaos magic, ritual drugs, sexual fetish, political protest. Not the kind of thing you talk about at work; not if you have the kind of job where you wear a suit.

Like me, most people on Barbelith were living a double life, a secret identity, a phantom existence behind the official day-to-day. Separate pages in a diary. But sometimes pages bleed through.

Most people on Barbelith were living a double life. Unlike me, most of them hadn’t genderswapped.

Except, it turned out, for the guy causing so much trouble. He emailed the site manager, Tom Coates, under the name ‘Andrea’, and confessed the password exploit. Their correspondence was made public.

Barbelith had a private message function, a back-channel behind its public discussion forums. Messages flew back and forward between the moderators, the manager and the veterans, sharing and collating information on DisInformation; trying to claw back some power from this guy who seemed to know everything about them. They pieced together details about his identity, and frantically pasted it into a dossier. One private message bled through to the main boards, posted in the wrong place by mistake, and before it was deleted, I saw a name I recognised; starred out like a curse word (‘A***** C****’) and then repeated, uncensored.

I recognised it, and the boundary between two worlds, the real and the virtual, suddenly collapsed. The barriers I’d imagined between Barbelith and my professional life, I realised, had never truly existed. I recognised the name from one of my class registers. The guy under the name DisInformation was a first year student called Andrew. I taught him.

I went through all my posts that morning, erasing and revising any giveaway clues – I’d even written about a specific class, on John Ford, that Andrew had taken part in. Barbelith was a large discussion board, and I hoped he hadn’t read every detail. I emailed the moderators, the manager and the veterans, telling them I knew who this Andrew was; I knew his email, I knew what he looked like, I knew, roughly, where he lived. They invited me to their private discussion room and took my evidence very seriously. It was exciting, like being a boy witness surrounded by grave but kindly policemen. They thanked me for letting them know, and said they would act on it.

Then I went to work, and taught Andrew as usual, except of course nothing was usual and nothing was the same. Whenever he spoke, I studied his face, wondering what he knew about me; wondering if he knew I knew.

At the end of class, he approached me at my desk, and I prepared myself. But he just gave me a video cassette – this was 2000, or ‘the year 2000’ as we said at the time – and awkwardly told me he thought I’d find it interesting. I imagine we both blushed. Fortunately, he left the room.

In fact, I later realised, he left the university that day.

I watched the video at home. I couldn’t screengrab it, of course. It was a video, on a television. But I took a photograph of it, on freezeframe, then had it developed and stuck it in my diary.

He was in a forest, dressed like Neo from The Matrix. There was a lot of rhetoric about conspiracies, government cover-ups and what humanity would need to do to survive in the 21st century; the kind of thing he wrote on Barbelith. After ten minutes, I fast-forwarded it to the end. Nothing but static and snowstorm.

Andrew dropped out from college, and DisInformation was finally banned from the boards. I never heard from him again, though I searched for his name a few months later (I would have said I googled it, but it probably wasn’t Google, at the time) and found a blog of travel photos, showing him in various locations around the world.

My credibility was boosted on Barbelith and I became regarded as one of the big players, the iconic characters, until the boards declined and collapsed, overrun with spam and deserted by the regulars. You can check it out now at www.Barbelith.com and see what I mean. My old posts are still there. In the real world, I got promoted and continued to climb.

I wish I could give you a better story. I don’t know how much Andrew knew of me; whether he’d witnessed my branding as ‘Dr Batman’ and decided to make himself into a kind of online supervillain, a worthy enemy. He was Welsh, and he could have been in Cardiff at the same time as me; he would have read the local newspaper stories, even seen my lectures. Perhaps the whole online performance was for my benefit. Perhaps that’s vanity, and the crossing of our paths, online and in real life, was just coincidence.

I’d like to give you a better story, a better ending. But this is a true story, and true stories never end.

About the author

Will Brooker is editor of Cinema Journal and author of several books including Batman Unmasked (2000) and Hunting the Dark Knight (2012)