“Destiny in Bangkok”

by Bruce Sydow

Headquarters calls it R&R for rest and recuperation, but the troops call it I&I for intoxication and intercourse.

Whatever the name, it is our reprieve from the fighting and we want to make the most of it.

Seated on a stage with ten Thai beauties, Destiny looks up when her name is called and squints into the lights like she is in a police lineup.

She is twice my age and is wearing nothing but a jewel encrusted sombrero, chaps, and spike heels.

The cowgirl takes me by my lead rein with the authority of Linda Evans in The Big Valley guiding a spooked horse through a canyon infested with rattlesnakes.

An hour later I am walking with a hitch in my giddy-up, and she is wearing nothing but a heavy-lidded smile.

All of 19 and the runt of the litter, I make my fellow Marines proud that night.

My grandmother back home, not so much.

About the author

Bruce Sydow has been published in numerous books, literary magazines, and anthologies including Penduline Press, Switched-on Gutenburg, andWriting by American Warriors. He served as a door gunner in a Marine Corps helicopter attack squadron and was decorated with the Combat Aircrew Wings, United States Air Medal, and Gallantry Cross. Bruce has held faculty positions at Saint Martin’s University and Chapman University, among other colleges, was elected Professor of the Year twice, and received the Excellence in Teaching Award.

“Firefight”*

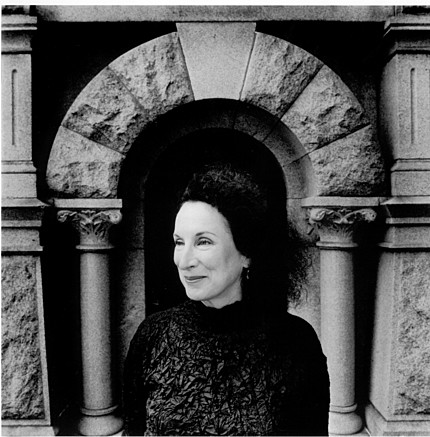

by Rebecca Goodrich

“This, ladies and gents, is an M60: a 7.63mm, lightweight, air-cooled, disintegrating metallic link belt-fed portable or tripod-mounted machine gun designed for ground operations.” A staff sergeant with ropy forearms hefts the gun with both hands, performs two biceps curls. “Eighteen pounds of pure rock and roll.”

It’s 7 a.m., mid-morning by military reckoning. Two hours ago a drill sergeant played reveille on garbage can lids and since then I’ve showered, dressed, run two miles in Army boots, wheezed through sit-ups, push-ups, six-count burpees, eaten baking powder biscuits smothered in milk gravy, and apple pie for breakfast. Now I stand at parade rest at the crest of a hill surrounded by undulating acres of green, heels shoulder width apart, hands in the small of my back, listening to a lecture on firing-range procedure.

I’m eighteen—I have never known guns before boot camp. Never tasted red dust, inhaled the resiny note of longleaf pine, wilted under the oppressive weight of southern mid-day sun. Before this I’ve experienced little outside the damp borders of the coastal northwest, but a month ago, in May 1979, the U.S. Army paid my way to Ft. McClellan, Alabama. Here the air swims with the scent of blooming camellia, the heat makes my brain buzz, and the red grit on my tongue tastes faintly like blood.

Months earlier as a recruiter leafed through the list of available military occupational specialties, I asked for “a job as close to combat as a girl can get.” To his credit he didn’t laugh; he’d recruited enough confused country kids to know exactly what I meant, even if I didn’t. This was 1978. Vietnam was still a wound barely healed, a collection of images and stories yet to be revealed over the next two decades. My naïve wish for something like combat was an atavistic response to the cramped and prescribed boundaries of a girl’s small-town life. My first airplane flight had been only two weeks before: Seattle to Alabama— more escape than means to a destination. My enlistment contract read 95B: Military Police. Not because I had any aptitude for law enforcement; only because it sounded “exciting.”

The gun takes two of us to operate, one to pull the trigger and one to feed the linked belts of bullets into the ratcheting chamber. The barrel is wrapped in a perforated metal grid that keeps it cool. The finish is opaque gray. The stock is heavily padded and presses into the socket of my shoulder. Prone behind the trigger, thigh to thigh with a Detroit kid named Davis, I limber up my index finger. His job is to lightly guide the rattling belt of bullets that whip through the dust while I aim and fire at the large square of white paper downrange.

“Maintain your trajectory at target level,” the rangemaster harps. Every sixth round in the belts is a red-tipped tracer. It holds a hot, phosphorescent charge that burns white in daylight and illuminates the normally invisible trajectory of the bullets. In a few moments the range will appear strewn with ropes of tiny white lights strung from barrel to target. The maximum effective range of each round is 3,600.1 feet but at the right moment, on the right day, a bullet might travel over two miles before gravity defeats velocity. “Keep those tracers out of the wood,” he warns. “It’s been a dry spring.”

I grip the heavy handle with slick palms, wait for the command to fire, hear the bark of the loudspeaker, then squeeze. Inches from my face, in a chamber the diameter of my little finger, expellant ignites and explodes 9.17 times per second, 550 times per minute. Gas expands with each blast. Projectiles rifle through space 2,800 feet per second. My teeth clatter and my eyeballs jump. I feel unhinged and rearranged—I am pushing every lame-wheeled shopping cart in the universe. The barrel fights to rise. My biceps bunch and burn to hold it level. I breathe once, squeeze again and watch the red-hot rain of rounds and tracers arc through Alabama air. The targets riddle and shred before my eyes.

“Cease fire, cease fire!” The command from the range tower cuts through the chaos. The sun has moved high overhead. Far beyond the targets, out of the rolling green lifts a slender spiral of white, and I imagine I can detect the faint, singed-tinder smell of fire. A buzz travels down the line, something’s burning…someone dropped a tracer in the woods. Drill sergeants spring like they’re bee-stung, clearing the range of weapons, amassing us in formation, gathering in a knot, gesturing among themselves toward the thickening tendril of smoke.

“You, you, you, you,” one sergeant prowls down the line. “Line up here.” Twelve of us break rank and run, arranging ourselves in two lines. I am swept along with the squad, too dazzled at being chosen to wonder what’s in store. “Forward, h’arch.” We step out, down a two-wheel dirt track. Our boots drum a dusty cadence on the thick red dust. “Double time, h’arch!” We trot downhill toward the smoke.

In two minutes I am out of breath. I often lag behind the pack during morning runs, but today I will not suffer the humiliation of one who can’t quite keep up. We pound down the dirt road in unison, raising a cloud of fine red grit that rasps my eye, works its way between pursed lips. Around our waists we each we each wear a web belt and an assortment of gear: canteen, rolled plastic poncho, flat folding shovel in a green canvas case. My one-size-fits-all steel helmet jounces painfully as I shuffle in time to the drill sergeant’s called cadence.

Then the smell of road dust becomes mingled with the fresh-lit cigarette scent of fire. The blaze is out of sight; it’s the aroma of burning resin that shows where to enter the forest. I’m winded from the run but now I become aware of another sensation—a coffee-on-an-empty stomach fizz of adrenaline that makes me quiver. We enter the woods, treading as if we expect the long needles and cones to ignite beneath our feet. These trees are all spindly second growth, angled half-fallen trunks and bare, tangled limbs. The duff is spiked with clusters of needles and foot-long cones glistening with pitch. Nothing feels alive in this dim understory. We unsheathe our shovels, unbend the metal handles, and I wonder if any one of us actually knows what to do once we find the blaze.

Ahead, small flames sprout from the litter in a fifty-foot circle. “Fan out,” the drill sergeant points us toward the fire. “Just beat the hell out of every flame you find.”Within minutes the flames have danced themselves higher and spread farther. The fire fighting seems instinctive—an ancient, adaptive response to fire gone out of control. I remember the fire I started as a child when I was supposed to be burning trash, tempted by matches, wasted paper, and dry stems of grass. What followed was a heart-pounding, boot-stomping frenzy that left me shaking, and a burned circle of pasture.

“Make a fire line, like this.” In a reversal of authority one of the trainees has taken over. He seems to know exactly what to do, and the rest of the squad follows his lead. We turn the shovel blade ninety degrees and lock the collar with a twist. Shoulder to shoulder with the others I stoop and hoe, scraping the forest floor to bare dirt. Behind us others beat the life out of each glowing spark. One section of the fire circle dies, then another springs to life. Laughing and reckless, we hack with more energy than the flames demand. There is a rhythm to our assault, an instinctive choreography of advance, reconnoiter, regroup, that we didn’t learn in basic training. One boy trips backward into a bed of glowing cinders, but two more lift him before he knows he’s down. Three advance on a new flame, five follow behind, a few patrol the areas we’ve covered. My original adrenaline-spiked fear has mellowed into a fierce confidence, and I feel as if I could fight fire forever. When the drill sergeant blows his whistle I check my watch and find that we’ve been at this for four hours; it seems like a fraction of that time.

The danger is over. The understory is still warm to the touch, still smells charred and resinous. Only now do I realize that my uniform is wringing wet, pocked with holes and singed around the trouser cuffs. My chest aches, my eye sockets seem lined with sandpaper, and my face feels swollen and sore. Our drill sergeant reports in by two-way radio that the blaze is under control. An olive-drab troop bus pulls up in a gritty billow and we climb on, mute, wrung out. As I lift my boot to the first step I notice my prized spit-shine has dulled to ash.

Evening heat settles around Company E, 12th Battalion like wool. As the bus pulls up, our off-duty friends lounge on the concrete steps of the barracks, smoking or learning to smoke. Dinner finished up an hour ago; the mess hall is closed and any leftovers have been discarded or sealed up. All the mess sergeant can offer us is a loaf of white bread, two sticks of margarine and a butter knife. I raise my buttered bread and find a perfect black handprint on white.

Others crowd around, eager to hear about the fire. They spent the day picking up litter; we spent the day on the front lines and have news to report. This is another new sensation in a day of sensory awakenings; being the center of attention for some risky physical feat. Ordinarily I hang in the background, but tonight I describe the flames, the smells, the burns, the boy who tripped, his rescue. Our features are dusky with whorls of soot, like camouflage paint. Someone passes me a cigarette, the first I’ve ever tried, and instead of declining I lean over the dancing flame for a light. Why not? I feel invincible, as if I’ve been to war.

* “Firefight” originally appeared in the print anthology A Mile in Her Boots: Women Who Work in the Wild.

About the author

Rebecca Goodrich served in the U.S. Army as a Military Police for six years. These days she teaches creative writing and digital storytelling at Washington State University.